From recess-filled days to class at sunrise, school around the world can look very different than it does in the United States

This Is What a School Day Looks Like in Other Countries

Finland: Triple the recess, hold the homework

Elementary students in Finland spend around 75 minutes at recess, compared with just 27 minutes for American children. The thinking goes: Children don’t learn if they don’t play, so they have to play—every day, even if it’s cold. Finland, one of the countries in the world with the best schools, is internationally recognized as a model for progressive educational philosophies, and the general rule of thumb is 15 minutes of recess per hour of work. Believe it or not, students don’t even start actual academics until the equivalent of America’s second grade, and play is considered more important than homework.

Finland has quickly risen up the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test-score chart over the past few decades, which is why American schools are now trying to emulate their methods. That said, American schools have a long way to go in terms of de-emphasizing standardized testing and preparing kids for real life. In significant contrast to American schools, Finnish students don’t take standardized tests until they graduate from high school. Teachers are also held in incredibly high regard in Finland, much like doctors in the United States.

The Philippines: School in shifts

There are two “shifts” of schooling in many schools in the Philippines, with one starting quite early, between 6 and 7 a.m., and the other starting after lunch. As one teacher explained in an article for Connected Women magazine, she starts preparing for her day at 4 a.m. due to this double-shift schedule. The schedule is an attempt to solve the problem of overcrowding and the lack of space due to poverty in the country.

Teachers frequently have to deal with 65 children at a time, and sometimes there aren’t enough chairs or desks for everyone. “While the rich can send their children to private institutions with air conditioning and computers, rural public schools often have to make do without reliable electricity, and classes are sometimes held outside or in the stairwell,” according to Reuters. The two types of schooling are vastly different.

Marie Van Skaik is a Cincinnati mom and nurse who grew up in the Philippines and attended a somewhat rural school, in which grades one through six were together in one classroom. The groupings in the class were based entirely on intellect, she says, with the “smart kids” in group one and those who were “not so good at school” in group six, with descending levels in between. She says that while it worked well in one sense, because you weren’t competing with people who weren’t at your level, she would have “felt dumb” if she had been placed in the lowest group.

In Van Skaik’s school, students in her class went home for lunch, which was about a five-minute walk, and enjoyed snacks packed by their mothers during recess, where they also played hopscotch and similar games. In terms of classes, some were taught in English and some in Tagalog. While most students knew English after a few years, they didn’t practice it often. She also recalls large holiday celebrations at school, including gift exchanges at Christmas and festivals and parades in the spring.

United Kingdom: A few extra hours of shut-eye

Many American high schools are well underway before kids in the United Kingdom are even getting ready for first period. Paul Stevens-Fulbrook, who has been a high school teacher in the United Kingdom for nearly a decade, says that schools typically begin between 8:45 and 9 a.m. One school in London even moved back to a 10 a.m. start time after research showed that students learn better later in the morning.

Once they get to school, students refer to teachers as Sir or Miss, which Stevens-Fulbrook says feels a bit odd. “Most male teachers have never been knighted by the queen, and married female teachers don’t usually go by the name ‘Miss,’ but teachers are never called by their first name because we are English,” he explains. “Therefore, we do lots of pointless things because the powers-that-be fear anything that we didn’t do in the days of the British Empire.” Formality is also a key element in many classroom settings. “Sadly, high fives, fist bumps and one-on-one dance greetings are not prevalent in classrooms, apart from my classroom,” Stevens-Fulbook says.

Singapore: Major testing, major success

Across multiple standardized test models, Singapore students have been labeled “the smartest.” The country’s traditional lecture-based learning process boasts major success, but it also has kids taking life-changing tests as early as primary school. Students have already been “tracked” into lower- and higher-achieving brackets by age 12. Movements are underway to remake the education system to de-emphasize grades and reprioritize skill-ready future employees.

According to the Ministry of Education in Singapore, changes are coming: “We have been moving in recent years towards an education system that is more flexible and diverse. The aim is to provide students with greater choice to meet their different interests and ways of learning. Being able to choose what and how they learn will encourage them to take greater ownership of their learning. We are also giving our students a more broad-based education to ensure their all-around or holistic development, in and out of the classroom.”

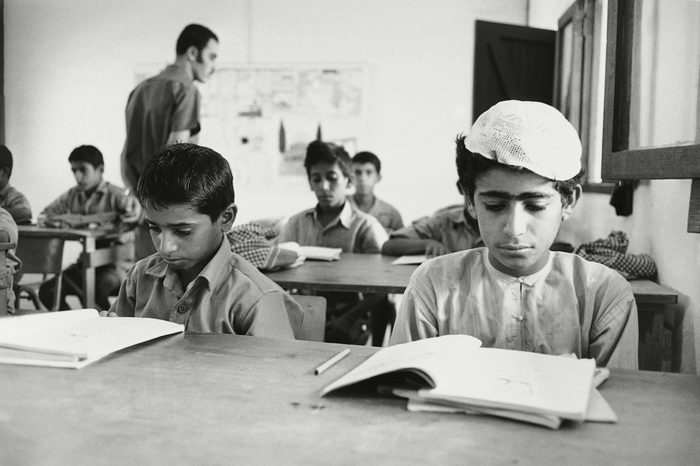

United Arab Emirates: Segregation by gender

Every country carries varying expectations for teacher-student relationships. Allen Kenneth Schaidle, a native of Illinois who has taught at Zayed University in the United Arab Emirates and served as the Director of Student Services at the American University of Iraq, notes that many schools are segregated by gender and that social norms for how a male teacher is allowed to interact with a female student are “quite rigid.” A casual relationship is not seen as culturally appropriate in Islamic countries, so there tends to be a more formal and professional relationship between teachers and students.

When it comes to career paths, parents encourage things like law, business, medicine and engineering over the arts, humanities and teaching. Maybe that isn’t all that different from some parents in the States, but there is a different expectation in terms of how children follow those directives. “Therefore, learning how to encourage students to follow their passions while also being respectful to the parents’ expectations is a difficult situation,” Schaidle says.

Iraq: Learning in a conflict zone

Schaidle also spent time in Iraq at a university in Iraqi Kurdistan, which included a student population of Iraqis, Kurds, Yazidis, refugees from Afghanistan and Syria, and a few Kurdish-Americans. He remembers change, not stability, characterizing the country as a whole, which he says “sadly trickles down into the country’s educational institutions, especially within the northern region of Iraqi Kurdistan.” Tensions impacted the educational environment as well.

“Cultural dynamics between the populations can be completely foreign to outsiders, and nothing comparable to social-group relations in the United States,” explains Schaidle. “For example, when the Kurdish Regional Government would push back against the Iraqi government, students would fight among each other along their cultural or ethnic allegiances.” In addition, students often had to take breaks to “step into the fray,” which is common for students in conflict zones. Sometimes they would leave temporarily or permanently to join Kurdish forces fighting ISIS. This dynamic is one that he said was “uplifted” by Kurdish society, so educators had to be sensitive to these changes.

Thailand: Mandatory haircut

In Thailand, schools are joyful and welcoming spaces filled with smiles and laughter, according to Oliver Crocco, an associate professor of Leadership and Human Resource Development at Louisiana State University who previously taught at Payap University in Chiang Mai, Thailand. He says the main differences between Thai and U.S. schools reflect the countries’ collectivist versus individualist cultures. In Thailand, for example, students typically sit at desks with other students, rather than individually, and group learning is “productive and effective.”

Surprisingly, students may often be on their phones or even answer phones in class, and there is also a lot of talking while class is in session. While Crocco says it may appear disorderly or chaotic to Americans, this works in Thailand. And this behavior shouldn’t be confused with disrespect, as the country holds the teachers in very high esteem. There’s even a special ceremony for teachers on a national holiday called Wai Khru, when students prostrate themselves before their teachers and provide them with flowers, in alignment with the hierarchical culture there.

Another notable difference is that students do not wear shoes in the classroom, and even some hallways, and there is a uniform in most schools. “In places like Chiang Mai, the governor also asked that all students wear traditional Northern Thai clothes on Fridays,” Crocco says. “Boys are required to have certain haircuts. In the morning before school at the beginning of the year, you can hear teachers shaving boys’ heads who don’t meet the requirements.”

Plus, in stark contrast to most American schools, sports are less of an ongoing daily occurrence in high schools. Instead, there are specific days in which schools compete in a variety of events, with little training ahead of time.

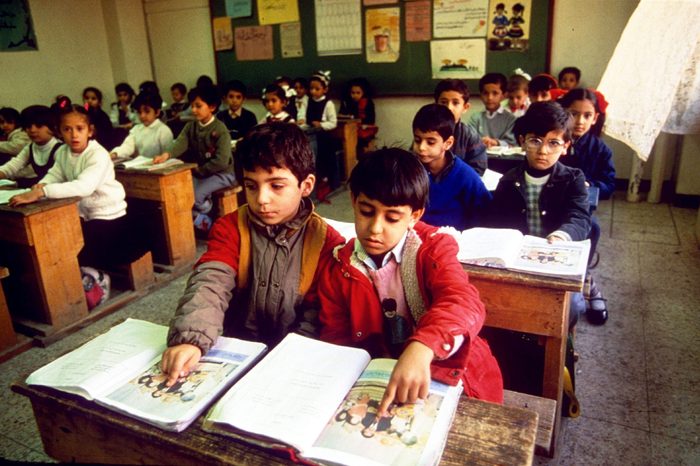

India: Lectures, respect and overpopulation

Anupriya Basu knows the Indian classroom well. Though she now lives and works in Canada, Basu attended school in India from kindergarten through college and says that there, lectures are the norm. “Most teachers maintain a certain distance from the students, and the communication between them is mostly about the coursework,” she explains. “In classes, the lectures are steered by the professors, and there’s little room for discussion or raising questions. Culturally, Indians tend to respect their elders a lot, and it’s frowned upon when a student cross-questions a professor.”

And while American students may think that high school is a grind, they may gain a new perspective after hearing about the experiences in India. “The days are jam-packed with classes, and students are expected to cope with sitting in classes without many breaks,” says Basu. Furthermore, students don’t typically explore elective classes outside of their main coursework to ensure they are focused and ready for their specific job market.

That said, education in India can vary greatly. While the country has the fastest-growing major economy, it is still developing and has the largest number of people living in poverty in the world. According to World Education News + Reviews, the country has high teacher-to-student ratios as well as high dropout rates. While progress is being made, the system is stressed by the country’s current “youth bulge.” There are currently 600 million young people in the country under the age of 25 (28% of whom are 14 or younger), and 30 babies are born every minute.

About the experts

|

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Anupriya Basu, senior content marketing manager based in Canada

- Marie Van Skaik, RN, Cincinnati, Ohio, mother and nurse from the Philippines

- Oliver Crocco, associate professor of Leadership and Human Resource Development at Louisiana State University

- Allen Kenneth Schaidle, strategist at a global growth strategy firm and former teacher at Zayed University

- Business Insider: “The 10 smartest countries based on math and science”

- Paul Stevens-Fulbrook, UK-based high school teacher and education writer at Education Corner

- New Republic: “The Children Must Play”

- Los Angeles Times: “Op-Ed: Why Finland has the best schools”

- Connected Women: “A Day in The Life of A Public School Teacher”

- Reuters: “Philippine schools offer hard lesson in life”

- Daily Mail: “School becomes first in Britain to change its start time to 10am to allow pupils to ‘fully wake up'”

- Ministry of Education, Singapore: “Singapore Education System”

- Business Today: “IMF sees India’s growth decelerating, but it will remain the fastest-growing major economy”

- World Education News + Reviews: “Education in India”