Go ahead and split that infinitive! Here are some of the grammar rules that have changed with the times.

12 Grammar Rules That Have Changed in the Last Decade

Default to the singular they when needed

One of the most significant shifts is the acceptance of they as a singular pronoun. It replaces clunky constructions like he or she and is both grammatically sound and inclusive. Think: “Each person went to their desk.”

The funny thing, says McLendon, is that this “new” usage change isn’t new. “They, as a singular for an unknown or unspecified person, has been acceptable in English for centuries,” she says. “Shakespeare used it. Jane Austen used it. Dickens used it. It’s in the King James Bible.”

More recently, the use of the singular they has become a way to respect nonbinary individuals who don’t identify with he or she. If you know someone’s pronouns, use them. If you don’t, they is just fine.

Know the lay/lie distinction is dissolving

One of the changes we’re in the middle of, according to McLendon, is the end of the whole lay/lie distinction. She explains: “You need to have a direct object with lay: ‘I’m going to lay the book on the table.’ And the past tense of lay is laid, so ‘I laid the book on the table.’ If I’m going to go lie down, lie doesn’t have a direct object; it is intransitive. The past tense of lie is lay, and the past participle is lain. And I tell you: No one uses that anymore.”

She adds, “People say, ‘I’m going to go lay down.’ But even if they use lie down, they use laid as the past sense of that: ‘I laid on the couch all day.’ And I think that whole distinction is collapsing because it was confusing to begin with.”

So go ahead and use laid as the past tense of lie. As a professor, however, McLendon still teaches the old rule, simply because “someone in your college career or your first boss will be a stickler who really insists on the distinction.”

Simplify to graduated school—no from needed

How people talk about finishing undergraduate degrees has changed. These days, notes Fogarty, people are saying “they graduated college” instead of “they graduated from college.”

What’s interesting, she says, “is that ‘graduated from college’ is a newer version than what was before that.” Our grandparents viewed graduation as something that a college did with someone—a college graduated a student. And so they would say, “Johnny was graduated from college.” However, our parents, older adults today, would typically say, “Johnny graduated from college,” without the was. “Now more and more and more people are saying, ‘Johnny graduated college,’ and leaving out the from as well.”

Fogarty says this shows that “language is getting simpler. We vote with our usage, and there’s a strong drive to simplify the language.”

Feel free to use over for numbers too

I was taught to use more than to refer to numbers and quantities (“More than 100 people attended the party”) and over only for spatial relationships or physical position (“The painting hangs over the mantel”). Apparently, that distinction is no longer required. Fogarty points out that a few years ago, the Associated Press Stylebook—the go-to authority for all things grammar and punctuation—decreed that over is acceptable in all uses to mean more than.

Split an infinitive if you want

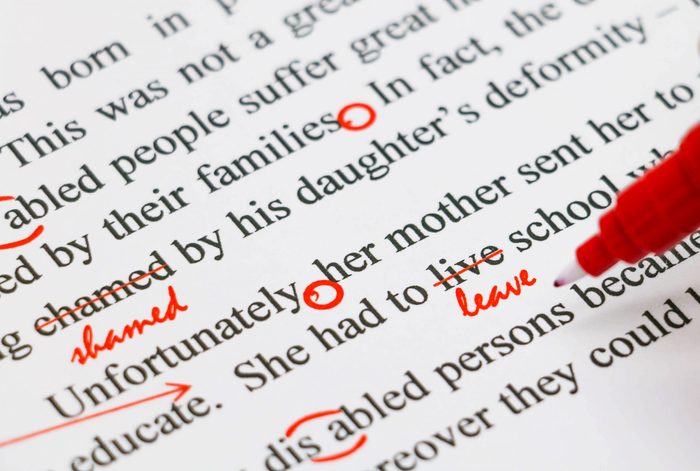

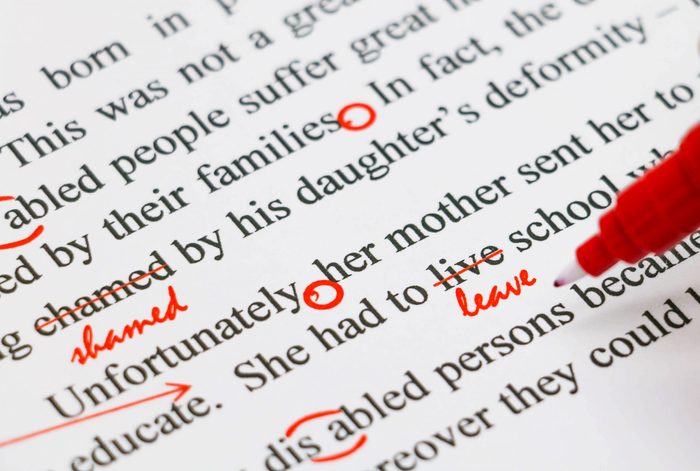

If you’re one of those people whose high school English papers were covered in red ink, complete with “Split infinitive!” written in the margins, you’ll like this news: The rule that you shouldn’t split an infinitive has changed. When you split an infinitive, you put an adverb between to and the verb, as in “to boldly go.” In short, to rampantly split infinitives is common and has become acceptable.

The goal is both to clearly communicate and to communicate clearly. As Fogarty notes: “You shouldn’t make your sentence awkward just to follow some rule that’s barely even a rule.”

Use respectful, people-first language

Recent AP Stylebook changes take into account progressive cultural changes in awareness and sensitivity. Don’t use terms like Whites, Blacks, the blind or the disabled as nouns. This kind of language can come across as reductive or dehumanizing, defining people solely by one aspect of their identity. Instead, use the descriptors as adjectives in phrases like “Black people,” “people who are blind” or “individuals with disabilities” to emphasize their humanity and acknowledge that that identity is multifaceted. Also, such information should be included only if it is relevant.

Don’t use Indian when you mean Native American

The term Indian refers to people from South Asia or India. When you mean Indigenous people of the U.S., use Native American as an adjective (not a noun). Better yet, use the specific name of the tribe (Navaho crafts, Lakota traditions, the Ojibwe community). McLendon puts it simply: “Ask people how they would like to be identified.”

Drop the hyphen in dual heritage identity

You should no longer use a hyphen in compound nationalities or ethnicities like African American or Asian American. “A friend of mine, the late Henry Fuhrmann, worked really hard to get the hyphens out of hyphenated Americans,” says McLendon. “He thought, ‘I’m Asian and I’m American. Asian should modify American. It shouldn’t be attached to it.’ And so he started advocating to take the hyphen out of any hyphenated American.”

The AP Stylebook made the rule change, eliminating those hyphens, in 2019. “It wasn’t a change for the sake of change. It was a change for a reason,” McLendon adds.

Skip the hyphen on some compound modifiers

The AP Stylebook recommends keeping a hyphen if it adds clarity and leaving it out if it adds clutter. McLendon’s rule: “If you have a compound modifier that is made up of two different parts of speech, you probably want to hyphenate.” Think, “high-fashion model”: High is an adjective and fashion is a noun. “Since there are different parts of speech, you hyphenate.” The flip side of that is “ice cream cone,” she says: Ice is a noun, cream is a noun. “They are the same part of speech, so you don’t need to hyphenate.”

Fogarty agrees with this trend. “We’re seeing fewer hyphens, fewer commas; language is getting simpler,” she says. “Modern English is far simpler than Middle English and Old English. There’s just a drive to make language simpler and easier to use, and so that just continues.”

Go ahead and start sentences with a coordinating conjunction

You’ve probably heard that you should never start a sentence with and, but or or. But maybe you do it anyway? And you’ve gotten away with it? Yet you still feel nervous when you break this rule? Relax. It’s fine. “Social media encourages us to be informal because we’re trying to convey that we’re having a conversation,” Fogarty says. “So we’re seeing informal writing a lot more than we used to.”

However, your audience matters. “You might not want to do it in an annual report,” where more formal language is expected, she cautions.

End sentences with prepositions, if you want to

Prepositions are words that indicate time, place and direction (at, for, by, of, on, in, after), and many of us were taught to avoid ending a sentence with one at all costs. Guess what? “If your sentence sounds more natural with a preposition at the end,” Fogarty says, “it’s fine to leave it that way.”

She adds, though, “If you’re doing formal writing, you should probably still avoid it, because a lot of people think it’s an error.”

Avoid whom (unless you’re super formal)

“People have been predicting the demise of whom for, I think, at least 100 years, and it hasn’t completely died out yet,” says Fogarty. “The average person doesn’t know how to use it and often thinks it sounds stilted. But I’m not convinced it’s going to disappear completely from professional writing.” Whom is still used in formal writing, but it’s feeling more archaic, like thy, thee and thine.

McLendon adds: “I tell my students, when in doubt, go with who at the beginning of a question. Who is fine. You know, ‘Who are you going to call?’ is just fine.” (Even if they don’t get the Ghostbusters reference.)

The moral of the story? “Proper English” has its place, but following every rule to the letter can make you sound stiff. “Grammar reflects actual usage,” says McLendon. “A lot of these things depend on who you’re talking to, who you’re writing for. You have to consider your audience.” So next time someone corrects your split infinitive or gasps at a sentence-ending preposition, just smile and say, “That rule died several years ago.”

About the experts

|

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. For this piece on grammar rules that have changed, Jo Ann Liguori tapped her decades of experience as a copy editor to ensure that all the information is accurate and current. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Mignon Fogarty, aka Grammar Girl, creator and host of the Grammar Girl’s Quick and Dirty Tips for Better Writing podcast; phone interview, June 9, 2025

- Lisa McLendon, professor of journalism and mass communications at the University of Kansas and creator of the Madam Grammar blog; phone interview, June 9, 2025

- AP Stylebook